News

The Story at the Heart of Japanese Culture: “The Tale of Genji”

Shimauchi Keiji

Updated in June 2021

The Tale of Genji has played a substantial role in the formation of Japanese culture, and has lost none of its radiance in the millennium since it was written.

Reading The Tale of Genji is an excellent way to understand Japanese literature, and the country’s culture in general. Its devoted readers over the centuries include Kawabata Yasunari, the winner of the 1968 Nobel Prize for Literature, whose writings were suffused with the Japanese sense of aesthetics. His protégé Mishima Yukio, seen as a strong Nobel candidate, also took ideas from Genji.

A Mammoth Work Covering 70 Years

While Japan’s oldest work of literature, Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), was compiled in 712, The Tale of Genji is its most widely read and has been most influential in shaping Japanese culture.

An entry in the diary of author Murasaki Shikibu shows that she was in the process of writing Genji in 1008. This was a similar time to the composition of the European epic poem The Song of Roland, some 200 years before The Song of the Nibelungs, and almost 400 years before Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

Murasaki served in the imperial court. Her father was a famous scholar and writer of Chinese-language poetry. At this time in Japanese history, politicians held effective power while nominally counselling the emperor. Fujiwara no Michinaga is remembered as the archetypal statesman under this model, and Murasaki served his daughter Shōshi, who was the wife of Emperor Ichijō. The poet Izumi Shikibu, known for her passionate waka detailing uninhibited love affairs, was also one of Empress Shōshi’s ladies.

Ichijō had another empress, having previously married Teishi, the daughter of Michinaga’s elder brother. In her court was Sei Shōnagon, another literary lady who wrote of her life in Teishi’s entourage in essays collected as The Pillow Book. Written in rival courts, Genji and The Pillow Book are considered twin pinnacles of Japanese prose.

The Tale of Genji is a mammoth work consisting of 54 chapters. The longer first part tells the life story of the aristocrat Hikaru Genji, while the second part focuses on his putative son and his grandson. Altogether, the narrative covers around 70 years. In the first part, Genji seeks to win happiness through love affairs, while the second part depicts men and women for whom romance brings no joy. It is a world lacking in reason that would not seem out of place in a modern novel.

Pleasure and Troubles

The Tale of Genji stands at the zenith of Japanese literature for its elegant phrasing, dramatic shifts, distinctive characters, memorable scenes, keen critical spirit, and poignant themes.

To give just one example of the work’s poetic language, the title of the final chapter, “Yume no ukihashi” (The Floating Bridge of Dreams), was later frequently reused in medieval waka and has served as a title in modern and contemporary fiction. Countless more phrases have influenced subsequent Japanese literature, as Genji has played a similar role to the Bible and Shakespeare in the Western literary tradition.

The story is rich in dramatic reversals. The protagonist Genji is dazzling in appearance, and born as the son of the emperor, but soon has his imperial status stripped away as a means of protecting him from court intrigue. He displays an almost supernatural charisma in a series of love affairs that seem to cover the full gamut of romance in world fiction, ranging from numerous adulterous entanglements with aristocratic ladies and even an empress to a tryst that challenges religious taboos and a liaison with a woman decades his senior. His fortunes repeatedly wax and wane like the moon, however, as he experiences both pleasures and troubles.

Genji becomes a traveler, leaving the splendor of the capital after an ill-advised affair brings political disgrace. He is forced to live in austere lodgings for a year in provincial Suma and a year and a half in nearby Akashi. This famous episode inspired a waka by Fujiwara no Teika,(*1) which in turn greatly influenced Sen no Rikyū when he was laying down the principles of the tea ceremony in the sixteenth century.

After Genji returns to favor and the capital, he has a mansion called Rokujōin built to house his wives and children. This comprises of four square sections, each 120 meters long, which represent the beauties of spring, summer, autumn, and winter. While visiting his loved ones, he can enjoy the charms of each season.

One of the rules of Japan’s well-known haiku poems is that they should include a kigo (season word), as taken from a special dictionary known as a saijiki. Genji’s Rokujōin is a first step on the way to forming the saijiki, which demonstrates the importance of the seasons in Japanese aesthetics.

A Continuing Influence Today

The protagonist encounters a host of characters in the story, all of them distinctive. Suetsumuhana is one such character: although highly born as the granddaughter of an emperor, she lives a straitened life. Her name in the story comes from the safflower, known for its red blooms, and is bestowed on her for the reddish hue of her nose—a play on hana, which can mean both “flower” and “nose.” Genji is dominated by tragic elements, including adulterous relationships that bring troubled children, but the red-nosed princess is comically endearing, and draws warm smiles from readers. Dozens more such singular characters appear.

There are countless unforgettable scenes. When he is well into middle-age, Genji’s new young wife starts an affair. She conceals a letter from her lover under a cushion, but Genji discovers it in a classic moment that has gone on to be regularly repeated in one form or other in narratives over the years since.

I quite often read later fiction and notice scenes that are modeled on incidents that I remember from particular chapters of Genji. In a sense, the work is an encyclopedia of Japanese literature. Even Murakami Haruki leans on the famous forebear in his international bestseller Kafka on the Shore.

The characters dissect civilization and society in many discussions. In a well-known early scene, a group of male friends gathered together on a rainy night try to define the ideal woman. Later, during a happy period at Rokujōin, Genji talks with others about the purpose of stories.

The inclusion of critical discourse in a work written in the early eleventh century shows that Japanese culture had reached a major peak in this period. The cultural ideal of the time of miyabi, or refined elegance, found expression in palace conversations between male aristocrats and intellectual court ladies, combining with sharp social observation to form a searching critical spirit. In the course of reading Genji, one naturally comes to consider what it means to live and be human.

Genji in Art

The main theme of Genji is how the pleasure of life turns to sadness at some point, as destiny’s ironies lead the characters into despair due to their failures to love others as they should. Some might object that this is a subject that appears in fiction from every age and corner of the globe. This is true. Yet readers are moved by how even Genji—blessed with unsurpassed good looks and every kind of artistic talent—cannot bring his lovers happiness and ends up suffering. This great and genuine sentiment, which lingers on after the book is finished, is the work’s greatest charm.

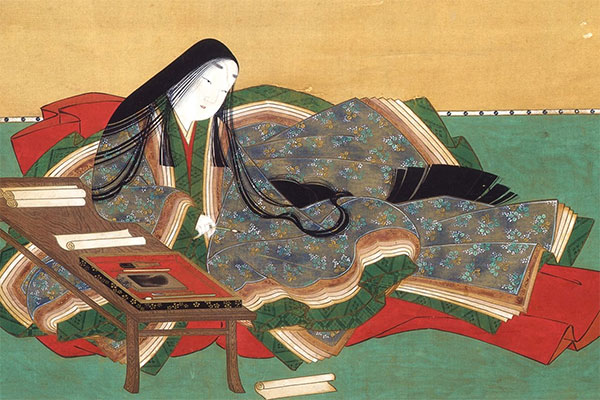

With more than a millennium of enthusiastic readers, Genji has had an influence in other arts, particularly the visual arts. Many fine picture scrolls and folding screens depict episodes from the story. Viewers familiar with the tale can try to recall when they took place from the court activities, personages, seasons, and scenery on display, reentering the world of the eleventh-century masterpiece to experience the exquisite sorrows of its characters’ lives. For those who have yet to read Genji, these artworks may inspire interest and the desire to dive in.

Like an encyclopedia or a well-stocked department store for the whole of Japanese culture, Genji awaits new readers, who will find its timelessly engaging riches of use in their contemporary lives.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 27, 2019. Banner photo: A detail from a folding screen shows Genji in exile at Suma. Courtesy Gakushūin University Museum of History.)

(*1) Miwataseba / hana mo momiji mo / nakarikeri / ura no tomaya no / aki no yūgure, translated by Lewis Cook as “Looking out across / the shore / no flowers, no autumn leaves / a thatched hut’s / evening of autumn.” Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, ed. Shirane Haruo, 2012.

Contributed by Nippon.com