News

Searching for Satori Updated in March 2021

I first heard about shukubō temple guesthouses on my first trip to Japan in 2003. The information in my guidebook said that foreign visitors to Japan could stay overnight at temples and practice Zen meditation and sutra copying. Ever since then, I had wanted to stay at a shukubō, and my wish finally came true last November, when I stayed at Taiyōji, a temple in Chichibu, Saitama.

Escaping the Bustle of the Big City

I chose Taiyōji, a temple in the city of Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture, as my destination because a Japanese journalist friend had previously reported on it. It was recommended as perfect for zazen beginners. The temple has a remote feel, but at just two and a half hours from Tokyo, it offers easy access as well.

But my journey started off poorly. Scheduled to meet up with a group traveling to the temple at Tokyo’s Ikebukuro station at 2:00 pm, I had dawdled, packing some warm clothing. When I got there and attempted to board the express bound for Chichibu with a regular ticket, I was stopped at the wicket and missed the train by a mere minute or so.

When I arrived at Seibu Chichibu Station after taking a slower train, the group had long since been met by a vehicle from the temple. Luckily, I was able to transfer to a local train and take a taxi to the temple from Mitsumine-guchi, the nearest station.

I was met by head priest Asami Sōtatsu, who greeted me with a warm smile. He told me that the group had just started a yoga lesson and offered to lead me to the hall once I had taken a moment to get settled.

Our group consisted of 22 people in all, 15 women and 7 men. While foreigners had often stayed at the temple before the coronavirus pandemic, this time I was the sole non-Japanese, making it an ideal opportunity to immerse myself in Japanese culture.

Everyone was chatting in a friendly manner, so I assumed that they all knew each other, but surprisingly, most people had come by themselves. I had always thought that Japanese were reserved when meeting strangers, but that didn’t seem to be the case here. A shukubō seems like a place where strangers quickly warm to each other.

I asked the others why they had chosen to come to the temple. One woman in her twenties related that she had quit her job to travel around the world. But that plan fell apart when the pandemic struck and now she was here, trying to figure out what to do next.

Another participant, a tall, solidly built young man, said that he had been a security guard but quit work after falling ill due to stress and overwork. He had recovered physically, but he had come to the temple seeking inner peace. I was surprised at the number of young people worried about their future who, seeking to calm their fears, had chosen a shukubō stay.

I was having personal problems myself, and I wanted to get a fresh start in an out-of-the-way place in the bosom of nature, far away from any cellphone signal. I also have an auto-immune condition that flares up under stress, and as I observed the always calm demeanor of the temple priests, I hoped to divine what their secret was.

Trying to Achieve Emptiness

After the yoga session, we returned to the main hall and began our training in earnest, starting with sutra chanting. The Heart Sutra in Zen Buddhism consists of only 262 kanji characters but it is the distillation of the Buddhist Mahayana teaching of the concept of emptiness.

In Christian religious practice, adherents respond after the priest’s or minister’s invocations, based on their understanding the words of Christ or Bible verses. It felt very strange to be reciting scripture that I did not understand at all.

Seated in front of a large Buddhist image, the head priest began to chant as he struck a keisu “singing bowl” with a thick baton. It all seemed like he was trying to bring the statue to life, and a shiver ran through my body. The priest, chanting rapidly, seemed transported to a different plane, as if mesmerized by the Buddha.

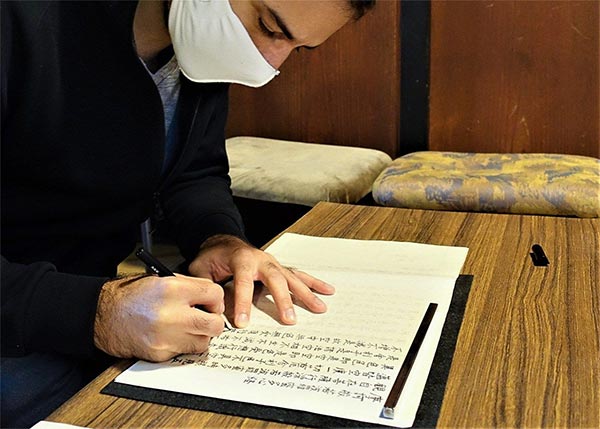

After chanting, we began copying the Heart Sutra. Tracing paper is laid over a model of the text, an exercise simple enough even for non-Japanese who cannot read or write the characters. After the sound of chanting, the room where everyone was concentrating on their copying work was hushed and still.

But even though I tried to focus on doing this one thing, it only took 5 minutes for my attention to wander. I couldn’t understand why everyone would travel so far just to sit and copy a sutra, and ultimately, it took me a whole hour to finish. At the end of the exercise, everyone wrote down a wish: mine was to understand why I had been doing what I had just done. In retrospect, it is obvious that the meaning of “emptiness” had passed me by completely.

And then, when I tried to stand, I fell in a heap onto the tatami. My legs had gone to sleep.

As I waited for the prickling in my legs to subside, two men invited me to go along with them to the outdoor bath in the garden. The sun had gone down, and there was a chill in the air. Since there was still time before dinner, I decided to get into the bath to warm up. The water smelled faintly of sulfur, and when I looked up at the starry sky, soaking in the bath felt like pure heaven.

Cooking and Eating Are Part of Training Too

I love any kind of Japanese food, and I really looked forward to eating temple cuisine.

Due to the Buddhist prohibition against the taking of life, temple food is vegetarian. But coming from a meat-eating culture, I was apprehensive as to whether it would satisfy my appetite. There was no nearby convenience store that I could run to if I still felt hungry after the meal. After yoga, chanting, and sutra copying, my stomach was rumbling, and I hoped the meal would be enough to see me through to breakfast the next morning.

I needn’t have worried. There were several dishes—kenchin-jiru stew chock-full of vegetables, simmered daikon radish with miso topping, a deep-fried patty of burdock and carrot, spinach in sesame dressing, deep-fried eggplant in a savory broth, and simmered freeze-dried tofu with carrot. There was just the right amount of food, and I felt sure I would sleep well.

But I had not thought of the cold. Taiyōji stands all by itself on a 800-meter mountain, and while it was 20℃ during the day at that time of year, temperatures plunged to nearly zero once the sun went down. I was sleeping in a drafty building built some three centuries earlier, not in a bed, but on a futon on cold tatami. I pulled the hood of my jacket up and piled on three blankets, but to little effect. I finally drifted off just before dawn, when I woke up with a start from a nightmare. In my dream, there was a Buddhist statue with a fierce expression next to my bed and I shouted out in fright. And with that, I woke up.

Later, as our group sat around a space heater in the main hall and I related my nightmare, one woman said she had seen an ogre in her dream and had been petrified, and a man described how he had been jolted out of sleep by the imaginary sound of a singing bowl ringing out. Our experiences seemed too plausible to be coincidence, so I concluded that the Buddha had been watching over us.

As I was the only non-Japanese in the group, many people struck up conversations with me out of curiosity about a foreigner attracted to Japanese culture. Anime and manga—Dragon Ball, Sailor Moon, Captain Tsubasa, and so forth—were my introduction to Japan. In France, every single cartoon I encountered was a Japanese work, and my desire to watch anime and read manga in Japanese sparked my interest in learning the language.

The Keisaku Stick Comes Down

Getting back to our training, the second day began with sutra recitation, followed by a session of Zen meditation. I’m not very limber, so I feared I would not be able to sit cross-legged, but the pose came to me more easily than I expected. I thought it might be thanks to our morning yoga session, or perhaps because the Buddha wanted to hasten me on the path toward enlightenment.

Sitting with eyes half-closed, with my gaze directed a couple meters ahead, breathing deeply, my back straight and my shoulders relaxed, I thought it would be easy to meditate. But instead of finding inner peace, I could feel my heart beat stronger and faster. I should have lowered my expectations instead of thinking that meditation would be good for me—that I would experience the world as I never had before. I was probably putting too much pressure on myself. I thought I would be a failure if I did not have some sort of mystical experience then and there.

Holding the keisaku, a flat wooden stick, the priest walked past me. Ordinarily, anyone who is unable to concentrate during meditation receives a sharp thwack of the stick on the shoulder. But at Taiyōji, it is only given to those who request it by bowing the head and putting the palms together in the gasshō pose when the priest passes in front of them. I thought he would go lightly since we were beginners, but I was wrong. The sound cracked like a whip through the silence. It felt as painful as a whip, too.

Actually, sitting up properly and breathing quietly after receiving the stick, I was able to experience calm, and the idle thoughts that had run through my mind gradually faded away.

The meditation hall sits atop a cliff, and one may sit facing the windows to meditate. As I gazed at the foliage starting to tint with autumn colors, I felt as though I were floating on a cloud—a reward from the Buddha, I thought.

It’s not possible to get deeply into Zen with just a one-night, two-day stay at a temple. Even so, I felt as though I had gotten a taste of “emptiness.” In other words, I had learned the importance of living in the moment, and I had discovered a spot where I could retreat to recalibrate when city life got to be too much for me.

When I returned to Tokyo, I related these thoughts to friends and family in France in an email. The next morning, I received a reply from my mother, who lives in the south of France, saying that once the pandemic subsided, she would like to visit Japan and go to Taiyōji.

Overjoyed, I replied, “Yes, do come in spring, and we’ll go to Taiyōji. Hitsujiyama Park nearby is a famous spot for cherry blossoms. We can also enjoy the vast expanses of creeping phlox with Mount Fuji in the background.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Composed by Amano Hisaki. Banner photo: Taiyōji, also known as the “temple in the sky.” The windows of the hall where visitors practice Zen meditation offer breathtaking panoramas. All photos by Amano Hisaki.)

Contributed by Nippon.com