News

Life at Wesleyan University Updated in June 2018

Joint Research with Nobel Prize Winner

In September 1971, Satoshi and Fumiko Omura departed for the United States from Haneda Airport. They were headed for Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. The population of Middletown was about 40,000. It is a typical prestegious liberal arts college in the eastern part of United States. Students and researchers were carefully selected for enrollment. One had to excel in order to get accepted. Graduates from Wesleyan included famed film directors, musicians, photographers, journalists, and artists. Many of the teaching staff were winners of the Pulitzer Prize.

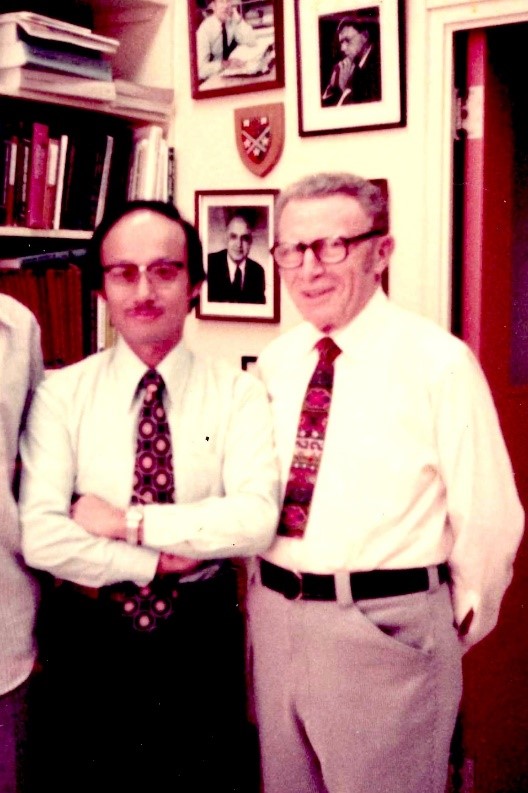

Omura’s salary was not high, but he was received as a Visiting Research Professor. A spacious private office was set up for him. Professor Max Tishler who accepted Omura to study in the U.S. was a a very open person, and he was also a reknowned figure in the world of chemistry.

In the fall of 1971, Omura had the opportunity to meet Konrad Bloch, who was a professor at Harvard and a recipient of the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his research on fatty acid. Omura explained that cerulenin, which he isolated and determined its structure, inhibited biosynthesis of fatty acids. Bloch showed great interest and they decided to collaborate. When Omura arrived at Harvard, there was a special desk laid out for him at the laboratory.

When Omura visited Professor Bloch’s laboratory, he was taken aback. It was so small and simple, that it hardly looked like a research facility of a great Nobel Prize winner. There was an ultraviolet spectrometer, and a PH meter to measure acidity or alkalinity. It did not look much different from Omura’s lab back in Japan.

At this point Omura realized that true research did not depend on sophisticated instruments and devices. You had to stand out with your ideas. This eye-opening experience had shaped Omura’s research philosophy in later years.

Omura also lectured at Wesleyan, but for his research, Professor Tishler asked Omura to do as he liked. Besides resolving the mechanism of cerulenin, he also focused on the chemical transformation of leucomycin, and collaborated with Wesleyan researchers to determine the structure of prumycin. Life outside the lab was also very satisfying and Omura enjoyed living in the U.S. with Fumiko.

Fumiko’s Activities on Campus

Omura’s wife Fumiko, who accompanied him to the U.S. had learnt English at a night-class of a local elementary school and in six months, she mastered daily conversation. Her bright personality also helped her communicative skills. She did not hesitate in whatever she wanted to do and her straightforward personality was welcomed by American people. She had become a popular figure on campus. Research staff and administrative personnel at Professor Tishler’s lab socialized like a big family. Satoshi and Fumiko often invited them to their house and hosted parties. Fumiko's caring hospitality was always appreciated by everyone.

One time, Fumiko was doing something intently in one of the chemistry classrooms long after activity hours had ended. When Omura peeked in, Fumiko was teaching how to use a Japanese abacus or soroban to Wesleyan students and staff. She distributed the soroban to all the participants. They had been specially ordered from Japan. This sight amused Omura very much. One time, Fumiko competed with a computer on her soroban. For the four arithmetic operations (adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing), Fumiko had beaten the machine. She had proudly recounted this incident to Omura when he reached home. Omura always enjoyed hearing Fumiko’s stories.

Collaboration with Merck

A year after Omura’s arrival in the U.S., in 1972, Professor Tishler was elected as chairperson of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS is one of world’s largest academic societies which retained about 100,000 members in the 70s. Current ACS membership exceeds 150,000. Tishler had also been a research director for Merck. Since then, he earned a great track record in fundamental research on chemistry that he was well known in relevant academic societies. After Professor Tishler became chairperson of the ACS, many more researchers came to visit. Because his boss had become too busy, matters at the laboratory was assigned to Omura.

At the Tishler lab, syposiums were hosted on a regular basis. This provided opportunities to interact with many top scientists. Well into the end of the two-year research term at Wesleyan University, Omura suddenly receives a request from Kitasato to return home. Omura wanted to remain in America as a researcher, but at the same time he felt indebted to go back to Kitasato Institute to continue his research.

Omura recalled how research expenses would be limited after returning to Japan. To solve this issue, he thought of securing research fund to his univeristy through joint-projects with American private companies. It was the standard way for laboratories in the U.S. to obtain funds. With Fumiko, Omura went around American pharmaceutical companies around Boston to propose joint researches. However, these companies could not come up with sufficient funds. Upon hearing Omura’s efforts, Tishler introduced Omura to Merck and collaboration had finally materialized.

In January 1973, with much achievements and many memories, and personal connections, Satoshi and Fumiko Omura left Middletown. The stay was a little less than two years, but during this time, Omura had co-authored six papers with Tishler.