News

Freezing to Save Flavor... and Life on Earth? A Look at Abi’s CAS Technology

Utsugi Satoshi

Updated in August 2021

When frozen food thaws, fluid drips out, carrying with it much of the food’s flavor. However, there is a freezing technology that can keep that fresh flavor from escaping. Developed by humble workshop owner Ōwada Norio, this technology, called CAS, is used in cutting-edge medicine as well as in the food industry.

Developing Technology to Please the Palate

Ōwada Norio, president of freezer maker Abi, humbly calls himself a workshop owner. His face remains impassive while he discusses his technology, but his voice displays his excitement. There is also a marked lack of jargon when he speaks. He explains that he never studied at any specialized engineering school. In his own words, his primary concern is how best to please farmers and fishermen, cooks and consumers.

“My father taught me to be a craftsman, so I can’t go pretending I’m some kind of engineer. A craftsman’s concern is putting a smile on the face of the future user, and that’s enough for me. I started out making patisserie kitchen machines and went around selling them for my father’s factory in Arakawa, Tokyo.”

In 1973, about seven years after he started working for his father, he was assigned to build something that could freeze fresh whipped cream. At the time, common wisdom said this was impossible to freeze for later use, as the low temperatures and defrosting process would cause the water to separate, leaving the cream as something like butter. At the same time, though, the challenge was an attractive one to take on: Whipped cream was difficult to handle fresh because of quick spoilage, and if it could be frozen, people could have their favorite creampuffs and other pastries any time they liked.

“I built machines, so I had no idea about ingredients or anything. I went knocking on doors at the companies making these ingredients to see if anyone would help me work on a freezer that could handle cream, and if they would let me come and study with them during the morning. Every place we visited said no until Fuji Oil, a vegetable oil producer, finally agreed.”

Ōwada studied with Fuji and went back to his own factory to work on designs with the older craftsmen there. In 1975, his efforts paid off with the world’s first freezer that could successfully freeze fresh whipped cream for later use.

A pâtissier in Japan who had studied in France discovered the newly available frozen cream and recommended it to an elite French vocational school. This led to the freezer being used in France, which then led to the interest of a chef recognized as a Meilleur Ouvrier de France (a prize conferred upon masters of cuisine and other trades) who went on to experiment with freezing various ingredients with the machine. The findings, though, showed that it could be used for pastries and nothing else.

“When I heard that, I flew to France and explained that since the freezer was aimed at cakes it wasn’t really useful for other fresh ingredients. They then said they’d help if I made a freezer that could work with other cooking. They figured that since I’d succeeded with cakes, I could do the same for fresh seafood and vegetables, too. So, I visited a Michelin-starred restaurant, where I learned just how important fresh ingredients are to French cooking. I really understood how ingredients frozen the usual way were unsuitable for it. The passion really inspired me, and I found myself wanting to make a freezer they would appreciate.”

Microwave Technology for Freezers

After leaving his father’s company to go independent in 1989, Ōwada continued his research and development on refrigeration technology. For high-end French cuisine, ingredients have to retain their natural, untouched flavor even after freezing. “Remaining edible” and “remaining delicious” are not the same thing. When ingredients are thawed, they suffer from drip loss—water containing flavor elements, like amino acids, flows out of it, weakening the flavor of the thawed food.

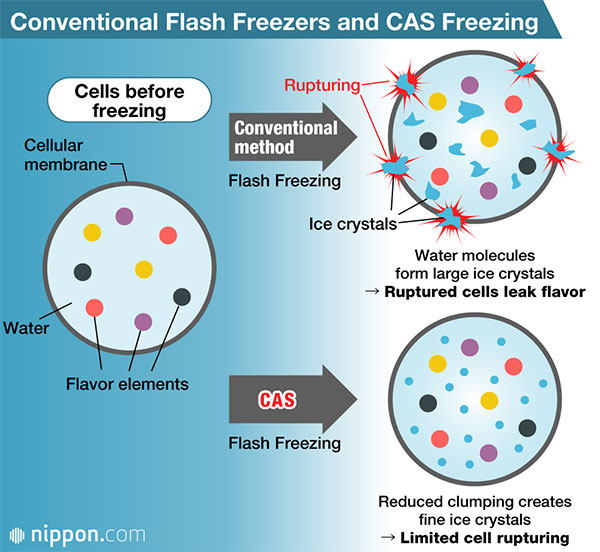

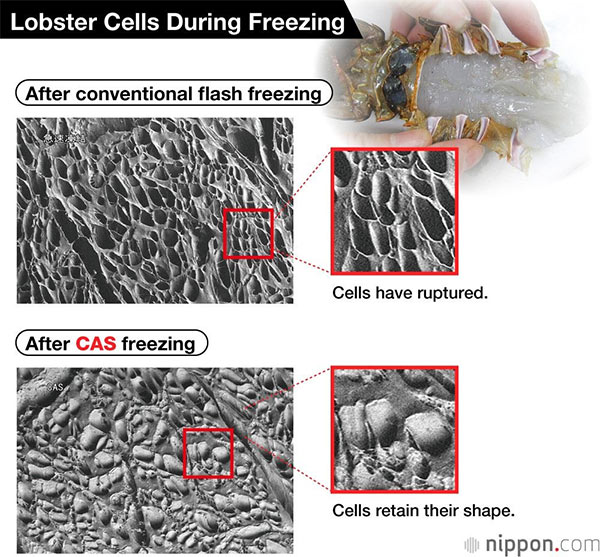

Ōwada guessed that the cause of that was the destruction of cells during the freezing process, and the main focus of his research was how to prevent that destruction. Conventional flash-freezing equipment uses wind chilled to –40 to –50 degrees centigrade, which rapidly cools the membrane of the cells but creates a temperature differential with the interior. He realized that this caused the cells to rupture, and dedicated himself to finding a way to chill both interiors and exteriors equally. That was when he thought of microwave technology.

“It occurred to me that if I could cool the inside and outside of the cells evenly, like how a microwave oven vibrates molecules to heat them evenly, I could preserve the original flavor. We could create a weak magnetic field inside the freezer to vibrate the water molecules and keep them from clumping together, and then we could freeze them all evenly!”

His prediction turned out correct. “In 1998 we succeeded in developing a refrigeration system producing no drip loss. The moment I ate that frozen food, and the fresh flavor filled my mouth, was such a happy one. At one point, development stalled, and we were in some real financial trouble, but right then it was like we’d discovered a time machine for flavor. We got a patent that same year.”

He named the magnet-based freezing system CAS, the Cells Alive System. It goes beyond simple freezing technology to actually preserve the flavor of food without damaging its cellular structure. The technology has undergone repeated improvement, and now makes it possible to preserve food freshness through installation in existing freezers.

“This is three years old,” says Ōwada, taking some raw whitebait out of the freezer for me to try. It tastes as fresh as fish caught that morning. Using CAS helps preserve fish, meat, vegetables, and fruit for long periods without any degradation of taste, color, or aroma. The technology can even be used to preserve wine and sake. Since the food’s cells do not rupture, its freshness can be kept as long as needed, and its flavor restored in full whenever wanted.

Overcoming Outlying Island Problems Using CAS

Currently, there are about 2,600 CAS units installed at places ranging from fruit, vegetable, meat and fish producers to food processing companies, restaurants, department stores, and supermarkets. The CAS food processing laboratory, located at Abi’s head office in Nagareyama, Chiba Prefecture, has continued improving the technology and developing low-cost equipment. They have also widened the range of places its advantages can be put to use.

For example, joint public-private companies in Ama, Shimane Prefecture, part of the distant Oki islands, are increasing sales of CAS frozen fresh squid and oysters through direct sales to the restaurant industry and consumers in the Tokyo area. The distance from the islands requires long hours of transport by ship and then truck, which has long been the greatest barrier to offering freshness. However, CAS allows producers to preserve fresh-caught flavor longer. The increased sales income for fishers is also helping attract younger people to the industry.

About 100 CAS freezers have also been installed in 13 countries abroad, with particularly frequent inquiries from the United States, France, Thailand, and China. France’s top chefs have tended to ignore CAS, but now Michelin-starred restaurants are using it to preserve ingredients.

Medical and Engineering Collaboration Growing

Since CAS can freeze without rupturing cells, it is also being used in medical research and similar fields. Regenerative medicine researchers are particularly interested, and are using it to preserve organs. CAS freezers are in operation at the Kyoto University Center for iPS Research and Application, and there are also joint research projects in engineering fields.

Ōwada says he hopes to spread the technology even further. He is not simply interested in growing his business, but believes that CAS could help solve inevitable future food crises.

“In twenty-five years, they say the world population will exceed 10 billion. We’re at 7.7 billion right now, and already there are 500 million to 600 million without reliable access to food. If you add another 2 billion people, imagine how out of control it will get. If we do nothing, then only the wealthy will have food. Farm harvests go up and down by year. The important thing is being able to store and stockpile crops when there is a surplus so that you can sell and buy more stably. That will make it easier for both sides of the transaction. CAS allows for long-term storage of fresh produce, ensuring that it tastes fresh-harvested when thawed. It can help reduce worries about price fluctuations for farmers, and consumers will enjoy more price stability.”

His dreams for the future of his technology seem like futuristic fantasy, but Ōwada has long-ranging ideas. “I think this technology could be useful if the earth becomes uninhabitable due to nuclear war or environmental destruction. Humans already have the technology to fertilize eggs. The eggs of various organisms can be frozen with CAS and sent out on spacecraft. Then, if an inhabitable world is found, those eggs can be revived, and the life of Earth can go on. It’s uncertain times like these, with the chaos of the pandemic, when we think about things that were considered only science fiction in the past.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Utsugi Satoshi. Photography by Nippon.com. Banner photo: Ōwada Norio explains the CAS mechanism at the food processing laboratory at Abi headquarters in Nagareyama, Chiba Prefecture.)

Contributed by Nippon.com